There are a number of problems with David’s ancestry:

- His legitimacy

- His Moabite ancestry

- Which tribe was he from?

First, there is the problem of his legitimacy. When the prophet-judge Samuel went to the hometown of Jesse to find and anoint the future king of Israel (1 Samuel 16), Samuel invited Jesse and his sons to a communal event. After seven of Jesse’s sons were introduced to the prophet, Samuel asked “Are all your sons here?” to be told, “There remains yet the youngest, but he is keeping the sheep.” (16:11). We never learn why David wasn’t invited along with his brothers to the event (“keeping the sheep” sounds like a poor reason to me for not inviting his son to such an important event. After all, when David’s brothers are fighting a battle [or actually not fighting because the Israelite soldiers were standing around afraid to confront Goliath] Jesse puts someone else in charge of the sheep while David is sent off to deliver cheese [yes, cheese!] to his brothers. The contrast is so obvious I’m sure it’s intentionally meant to be funny, another case of satiric humour in Samuel). In the next chapter, as part of the David and Goliath story, we discover that there is considerable animosity on the part of Eliab towards David, his younger brother (despite the delivery of cheese), but he aren’t told why. It makes me wonder if there was a reason why David wasn’t considered to be quite equal with his brothers. Then, in Psalm 51:5 [v.7 in the Hebrew], written (according to its title) by David after his adultery with Bathsheba had been exposed, he says “In sin I was born and in sin my mother conceived me.” Are there hints here that David was conceived out of wedlock, and that’s why he wasn’t recognised as being equal with his brothers (or half-brothers)? I’ve dealt with these questions more fully in an article here: “In sin my mother conceived me” – was David illegitimate?”

Then there is the problem of his Moabite great great grandmother, Ruth. It seems the whole point of the Book of Ruth is to give the back-story to David’s descent from a Moabite woman. For example, the story ends with the geneology of David and the very last word of the book is “David” which is perhaps a clue that his connection to the story may indeed be the very point of the story. This is potentially a problem because Deuteronomy 23:3 says “No Ammonite or Moabite shall be admitted to the assembly of the LORD. Even to the tenth generation, none of their descendants shall be admitted to the assembly of the LORD.” David was the third generation from Ruth, and definitely well within that “even to the tenth generation” restriction. Interestingly, the previous verse in Deuteronomy also precludes illegitimate children: “Those born of an illicit union shall not be admitted to the assembly of the LORD. Even to the tenth generation …” If I’m right about David’s conception then he would have been precluded on two grounds from being “admitted to the assembly of the LORD.” This phrase occurs only ten times in the Hebrew Bible, six of them in this short group of verses, and it is used elsewhere to mean “all Israel, the assembly of the LORD” (e.g. in 1 Chron. 28:8). It is possibly a cultic term, referring to Israel coming together for worship, but it is also used more generally for the nation at any time. In its context here it most probably means that the descendant of a Moabite is prohibited from being a citizen of Israel. How did David become King if he was precluded from citizenship?

The solution to this problem may lie in the hypothesis adopted by many biblical scholars that the book of Deuteronomy was actually written many years after the time of David, during the exile in Babylon. Deuteronomy is said to be a re-telling of the Law (in fact, “Deuteronomy” means “second law”), and it’s noteworthy that neither of these prohibitions are found in the “first telling”. Most biblical scholars argue that this is because Deuteronomy was written long after the time of David and the prohibitions against people born out of wedlock and descendants of Moabites were not in effect in the time of David. If this hypothesis is correct then it means David was not prohibited from citizenship (and therefore Kingship) in Israel, because there was actually no legal prohibition at the time. However, (and this is a big “however” in my view) this raises the very interesting question of why the writers of Deuteronomy during the exile would include two prohibitions to citizenship which effectively denied David’s legitimacy as king. Deuteronomy also includes “the law of the king” (17:14-20) which imposes certain obligations and restrictions on the king. This law is also unique in that it is not included in the other books of the Pentateuch, and therefore was not part of the law which was given to Moses on Mt Sinai. It also appears to be a direct criticism of Solomon’s kingship, which would only make sense if it was written after the time of Solomon, and would therefore fit with a composition date during the exile. Deuteronomy has a lot in common with the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings (which is why these books are called “the Deuteronomistic history”) and the prophet Jeremiah (which is also considered to be “Deuteronomistic” with some scholars thinking that Jeremiah [or his scribe Baruch] may have been the author of the Deuteronomistic history). These books are all critical of the kings of Israel and Judah, and arguably were written as a polemic against monarchy. I expect this would have been a hot topic during the exile for two reasons: first, the exiles would no doubt have been questioning what got them there, in exile, and who was to blame (kings seem to get the blame, especially one in particular); and second, if and when they ever return from exile should they restore the monarchy or ditch it as an institution which didn’t really work for them? If Deuteronomy was written as part of that debate then it seems to come down firmly against restoring the monarchy, and hence it’s not that strange that David and Solomon – Israel’s preeminent kings – are both denigrated.

As an aside, the book of Ruth is not considered to be part of the Deuteronomistic history. Although it is placed between Judges and Samuel in Christian Bibles it is in a separate section in the Hebrew Bible (in “writings” rather than with Judges and Samuel in “prophets”). Its author may very well have had a different view about David and kingship than the writer(s) of the Deuteronomistic books (although I’m not necessarily saying they did), or at least wrote in a different style, but that will have to be a dicussion for another post.

Finally, there is the question of whether David was a Judahite (from the tribe of Judah) or an Ephraimite (from the tribe of Ephraim). This point may come as a surprise to some readers, because it is almost always stated unquestioningly that David was from the tribe of Judah. After all, he was born in Bethlehem, which was in the territory of Judah.

The ancestry of David is provided in only two places in the Hebrew Bible:

Ruth 4:18 Now these are the descendants of Perez: Perez became the father of Hezron, 19 Hezron of Ram, Ram of Amminadab, 20 Amminadab of Nahshon, Nahshon of Salmon, 21 Salmon of Boaz, Boaz of Obed, 22 Obed of Jesse, and Jesse of David.

This lineage only goes back as far as Perez, but we know from elsewhere that Perez was one of the sons of Judah (Gen. 38:24-29; 46:12; Num. 26:20-21) and Ruth earlier (4:12) identifies this Perez as “Perez, whom Tamar bore to Judah.”

The only other record of David’s genealogy in the Hebrew Bible is in 1 Chronicles:

1 Chron 2:1-15 The sons of Judah: Er, Onan, and Shelah … His daughter-in-law Tamar also bore him Perez and Zerah … Hezron … Ram … Amminadab … Nahshon … Boaz … Obed … Jesse … David.

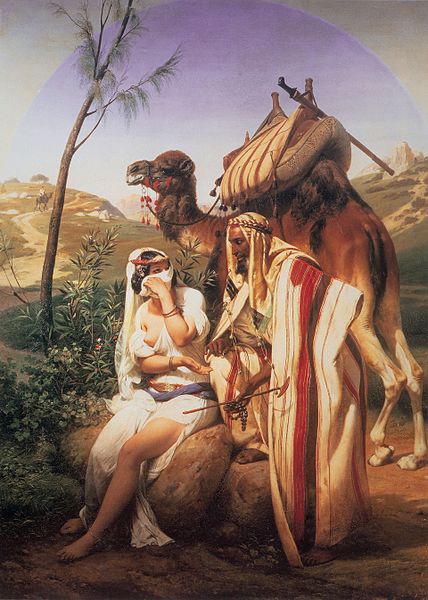

Few women are mentioned in the long lists of names in Chronicles, so one stands out: “His (Judah’s) daughter-in-law Tamar also bore him Perez.” We have to go back to Genesis 38 to get the full story. Tamar was the wife of Judah’s firtborn (Er). We aren’t given the details but the story goes that “Er, Judah’s firstborn, was wicked in the sight of the LORD, and the LORD put him to death” (v.7). The custom was that if a man died childless his eldest surviving brother would impregnate his widow and a child born from this union would be the dead man’s legal heir. Er’s brother Onan refuses to fulfil his duty and while he was happy to have sex with his brother’s widow “he spilled his semen on the ground whenever he went in to his brother’s wife, so that he would not give offspring to his brother” (v.9). We aren’t told why he did this – perhaps it was because of his brother’s wickedness that he didn’t want to give him an heir, who knows – but it gained Onan the distinct (dis)honour of forever being remembered as the one after whom the word “Onanism” was derived. The story is already becoming sordid, but it gets worse! As it unfolds, Judah later comes across his daughter-in-law sitting beside the road, mistakenly thinks her to be a prostitute, offers to pay her to have sex with him, and as a result she conceives a child. There are so many disturbing things here, not the least being that the morality of Judah offering to pay a prostitute he randomly comes across goes without any further comment thereafter! In fact, in a startling act of hypocrisy, when Judah learns a few months later that Tamar is “pregnant as a result of whoredom” he said, “Bring her out, and let her be burned” (v.24). Judah acknowledges that he did the wrong thing, not by going to a prostitute, but by forcing Tamar into this situation in not arranging for Er’s other brother (Shelah) to do what Onan refused to do. So many things come out of this story which we could explore, but my main interest here is why the writers of Chronicles draw attention to the sordid story in David’s genealogy – in a long list of names (of men) why mention this woman? It’s also interesting that these two prominent women stand out in David’s genealogy: one is a Moabite, and Moab was the child of an incestuous union between Lot and his daughter; and the other produces a child through the prohibited (and incestuous) union of Judah with his daughter-in-law. There are also several similarities between the Judah and Tamar story and the David and Bath-sheba story which are worth exploring (another time).

Chronicles also attributes the claim to David that he was explictly chosen as a descendant of Judah to be king:

The LORD God of Israel chose me from all my ancestral house to be king over Israel forever; for he chose Judah as leader, and in the house of Judah my father’s house, and among my father’s sons he took delight in making me king over all Israel. (1 Chronicles 28:4)

So according to Ruth and Chronicles David was descended from Judah through Boaz. Is this important? Even though Judah was Jacob’s fourth son (by his first wife Leah), he is depicted as the leader of his brothers (for example, in the story of Joseph); and in Jacob’s death-bed blessing of his sons Judah is promised that “your father’s sons shall bow down before you (Gen. 49:8). Also in that blessing is the statement that “the scepter shall not depart from Judah, nor the ruler’s staff from between his feet” (v.10) and this is taken to mean that the tribe of Judah would produce a line of kings. It’s possible that this blessing was written long after the time of David and incorporated into Genesis (and this is argued by many biblical scholars), but be that as it may, there are a number of biblical texts which refer to the tribe of Judah in connection with the Davidic kings. For example, Psalm 78 cites key events in Israel’s history and says:

68 He [God] chose the tribe of Judah,

Mount Zion, which he loves.

69 He built his sanctuary like the high heavens,

like the earth, which he has founded forever.

70 He chose his servant David,

and took him from the sheepfolds;

71 from tending the nursing ewes he brought him

to be the shepherd of his people Jacob.

It is odd, in view of the emphasis given to the Judah connection, that David’s ancestry isn’t detailed in the book of Samuel. In fact, Saul’s ancestry and lineage gets more attention in Samuel than David’s. In fact, the only genealogical information we get about David in Samuel are the names of his father and three of his brothers (compared with five generations of Saul’s ancestry, including their tribal affiliations). The most likely conclusion to be drawn from this is that the writer did not possess David’s genealogy, or else he would have included it.1

There is an oddity in the biblical descriptions of Bethlehem, the birthplace of David, which was geographically in the territory of the tribe of Judah. In a few places it is associated with Ephrathah or Ephrathites, including a famous prophecy by the prophet Micah:

But you, O Bethlehem of Ephrathah,

who are one of the little clans of Judah,

from you shall come forth for me

one who is to rule in Israel,

whose origin is from of old,

from ancient days. (Micah 5:2)

The phrase “Bethlehem of Ephrathah” is puzzling. We also find a similar term in 1 Samuel 17:12: “Now David was the son of an Ephrathite of Bethlehem in Judah, named Jesse, who had eight sons.” The same terminology occurs in Ruth 1:2 “The name of the man was Elimelech and the name of his wife Naomi, and the names of his two sons were Mahlon and Chilion; they were Ephrathites from Bethlehem in Judah.” Who were these people? The Hebrew word אֶפְרָתִי translated “Ephrathite” is a gentilic and can mean either “of Ephrath” (the name of the second wife of Judah) or “of the tribe of Ephraim”. Sara Japhet (who has written extensively on Chronicles and is regarded as an expert on the subject) has analysed all the uses of this term in the Hebrew Bible and has argued convincingly that in connection with Bethlehem the gentilic Ephrathite/Ephramite suggests that “David belonged to one of the Ephraimite families who settled in the northern part of the Judean hills, which eventually amalgamated with the Judean population and affiliated themselves with the tribe of Judah.”1 This would explain why information on David’s ancestry is scant, and only occurs in “late” texts (i.e. Ruth and Chronicles) which needed to make his Judahite ancestry absolutely clear.

The writers of the books of Ruth, Samuel and Chronicles all had their own agendas, and they weren’t necessarily the same. The Chronicler was almost certainly a Zadokite2 priest (or priests) who needed to establish Zadokite legitimacy and their priestly claim to rule Judea/Yehud after the exile, and hence they needed to avoid anything which would denigrate David and Solomon (a comparison of Chronicles with Samuel-Kings reveals that Chronicles left out anything which was remotely critical of David and Solomon, and exaggerated their good points). The books of Samuel and Kings, on the other hand, were critical of kings and monarchy in general, so portrayed David and Solomon “warts and all” and sometimes used satire, irony, sarcasm and humour to do it. Ruth, in my view, is also satirically humourous and may have been written in the same period as Chronicles, as a counter polemic to the claims of the Zadokites, undermining their exaggerated exaltation of David, in line with Samuel-Kings.

It is better, I think, to read the Hebrew Bible in this way as an ongoing dialogue between parties and scribes with their own vested interests, rather than as a consistent unit which requires hermeneutical gymnastics in order to harmonise every detail, even contradictory ones.

- For more information about David and Saul’s ancestries, and the term “Ephrathite” see Japhet, Sara. “Was David a Judahite or an Ephraimite? Light from the Genealogies,” Pages 297-306 in Let Us Go up to Zion: Essays in Honour of H. G. M. Williamson on the Occasion of His Sixty-Fifth Birthday. Edited by Iain Provan and Mark Boda. Boston: Brill, 2012. See also Nadav Na’aman, “Ephraim, Ephrath and the Settlement in the Judean Hill Country,” Zion 49 (1984): 325–31 (in Hebrew).

- The Zadokites were the forerunners of the Sadducees in the New Testament.